Location: 37 Tompkins Street, Cortland, NY

(42.5967896043635, -76.18206302698712)

The Carriage Door Entrance

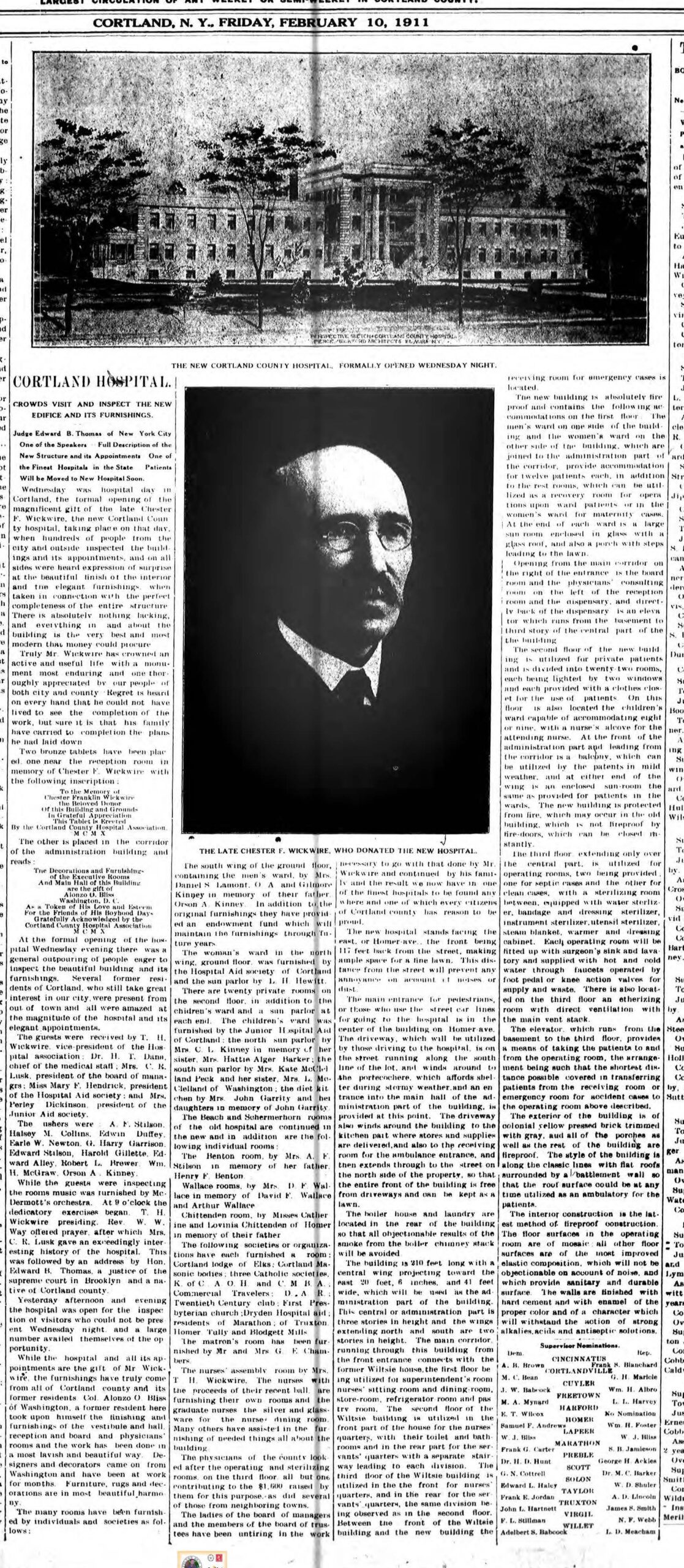

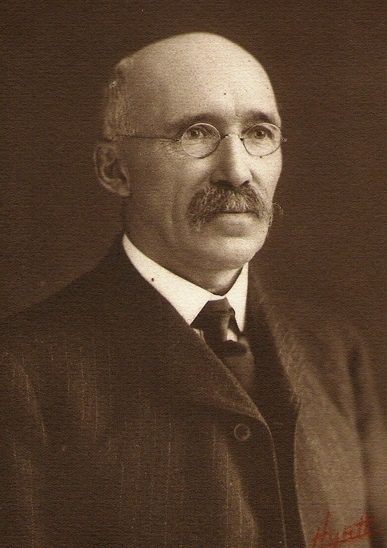

Monday, September 12, 1910, Chester Wickwire stepped through the grand carriage house entrance for the last time. Chester Wickwire shared his elegant home with his wife, Ardell, and their two sons, Charles and Frederic. According to the Cortland Standard, it was not an especially remarkable day at the start.

Mr. Wickwire had been in his usual health. He had been about his accustomed duties during the forenoon, partly at the wire mills and partly supervising some work at the new hospital on Homer Ave., which through his generosity and munificence is rapidly nearing completion.

September 14, 1910

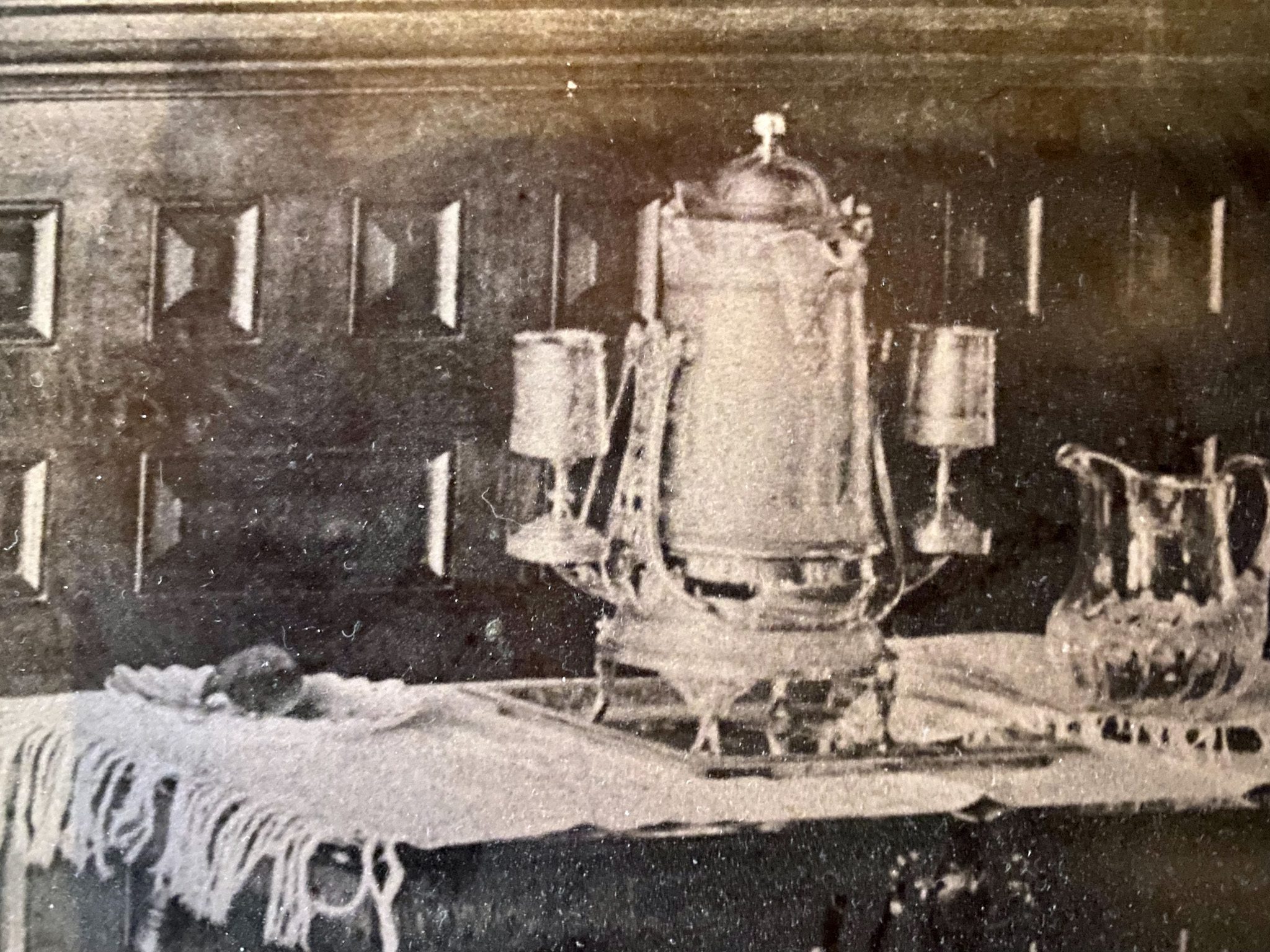

The Silver Water Pitcher

Upon entering, perhaps he stopped for a sip of water from the pitcher directly across from the carriage doors. A gift with a cheeky presentation from his employees 27 years prior. Many factories in Cortland at the time were experiencing unrest, with employees threatening to strike. On New Year’s Day, 1883, his employees requested an impromptu meeting with Chester, leaving him to fear the worst. When an unsuspecting Chester arrived, they surprised him with this silver pitcher to honor him for serving as an understanding, fair and kind employer. It seems only appropriate he spent the morning of his last conscious day, shoulder to shoulder at the factory with them.

The Cortland Democrat wrote, “Mr. Wickwire took unbounded pleasure in these mills and in their development. Always about them and among the men by whom he knew and loved and most highly respected, he was perfectly content.” (September 16, 1910)

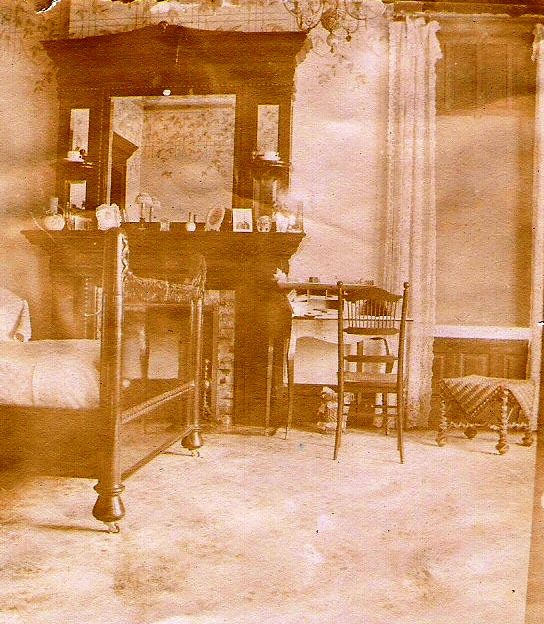

The East Parlor

According to the Cortland Standard, “He [Chester Wickwire] had returned to the house shortly before noon, had lain down for a few minutes on the lounge…” (September 14, 1910)

It’s easy to imagine a tired Chester stretching out next to a small fire, the glowing autumn sun catching the stained-glass transom windows, casting rainbows across the floor. The Cortland Democrat referred to Chester as “quiet and first of all home-loving.” In this room, his dedication to his family and home is obvious, as revealed in clever and thoughtful details though out the room. No expense was spared when it came to his family’s comforts in day-to-day living. One might assume it would be difficult to leave such a beautiful and welcoming space.

The Butler’s Pantry

This modest room was the butler’s pantry, a go-between from the kitchen to the dining room. Here, the staff would place the finishing touches on the Wickwire family’s dinner that fateful night.

At the time of Chester’s death, a small window existed between the butler’s pantry and the dining room to allow the staff to better serve and anticipate the needs of the Wickwire family as they supped. Designed so they could see, but not hear the family, it also provided them a silent witness to the tragic events that would unfold that evening.

The Library

The original dining room was converted into a library by Chester’s son, Fredric in the 1920s. Perhaps it was an attempt to wash away the vivid memories of that terrible night in 1910 that no doubt haunted him. A young man of 27 years, Fredric sat at the table in this very room for the meal that would become his father’s last. It was during this remodel that Fredric plastered over the window to the butler’s pantry, permanently obscuring the view from the servant’s prying eyes.

The Dining Room

Formerly the casual breakfast room, this space now possesses the original 15-foot solid oak table. Hand carved in the renaissance style, each chair bears the face of a “wild green man.” According to European lore, the Green Man is predominantly associated with the symbol of death and rebirth, an eerie talisman of what would unfold.

Chester Wickwire was seated at the head of this table, eating an ear of sweet corn, when catastrophe struck. “Suddenly, the ear of corn which he was holding fell from his hand, and a strange look came over his face. Mrs. Wickwire and their son Fredric, who were at the table with him, came to his assistance. He made the remark, looking at this right arm, ‘It feels numb. It’s paralysis all right.” (Cortland Standard, September 14, 1910)

The Stairs

Dr. Dana was summoned immediately and arrived within 15 minutes. With his aid, a still conscious Chester was brought up these ornate stairs, his gaze lingering over the elaborate banister across his beloved home for the last time.

According to the Cortland Standard (September 14, 1910), “Since then he has not spoken…he was conscious and followed with his eyes to those about him. It was an assured fact that a blood clot had formed on the left side of his head, where the nerves of speech are said to be located.”

His Son Charles and brother T.H. Wickwire were in New York City on business at the time and were immediately called for. His nephew, Arthur F. Stilson, would come to his bedside as well.

Chester’s Room

Lovingly, Chester was laid down on what would, unfortunately, become his death bed. Resting beneath the portrait of his son, Raymond, who was passed from Scarlett Fever at the tender age of 5, Chester drifted in and out of consciousness. As chronicled by the Cortland Standard (September 14, 1910) –

His nephew, Arthur F. Stilson, entered his room at about 6′ o clock last night, and the look in his [Chester Wickwire] eyes told of the recognition. With his left hand, he reached over and patted the right hand two or three times as though to intimate that the trouble was there.

At 10′ o clock last night, there was another cerebral hemorrhage, and since that time, he has not been conscious. At 2 o’clock this morning, a second hemorrhage occurred, and following that, the pulse became very weak, and it was thought he was going.

In a desperate attempt to aid the failing Chester, Dr. R. P. Higgins and Dr. Helfresh were summoned from Syracuse to the home, where they remained steadfast at Chester’s bedside until this last.

The report continued:

When one of the bad attacks came, an attempt was made to bleed him [Chester Wickwire], but the blood was thick and refused to run. There was another bad time at about 11 o’clock this more and then at the noon hour, he seemed easier, his pulse was a little stronger and he breathed better, but no permanent hope is taken from the fact.”

The Cortland Democrat wrote Friday, Sept. 16, 1910 –

A second hemorrhage in the evening and another in the night were the beginning of the end, his [Chester Wickwire] naturally strong constitution caring him through Tuesday, through Wednesday morning. His words on being stricken are explained by the fact that his physician [Dr. Dana] informed him last April that he must be extremely careful, and medicine was given to avoid what finally happened. Dr. Dana was in almost constant attendance after the first stroke, and Dr. Higgins and Dr. Helfresh of Syracuse were called in but Mr. Wickwire was beyond human aid.

The Clock

In the front of the entrance hall stands a magnificent Colonial Revival carved oak tall-case clock. Made by Tiffany & Co. of New York City, it has steadily kept the time for over 100 years. On September 14, 1910, as it struck the 5’ o’clock hour, Chester breathed his last.

That morning, the entirety of Cortland erupted into mourning. Heartbroken, the family began the arduous task of planning his funeral.

The West Parlor

The most ornate of the rooms was selected for Chester’s funeral, though there is no doubt the house must have received guests in its entirety to host the tremendous masses that came to pay their respects. The west parlor’s walls and woodwork are painted an airy gold and white. Imagine Chester, laid out under gilded ceilings, crowned with moldings resembling festooning ribbons, creates an ethereal mood.

The Cortland Democrat (September 16, 1910) said this of his funeral:

The funeral will be held at the residence on Tompkins St. tomorrow (Saturday afternoon) at 2’ o clock, but the house will be open from 10 o’clock till 1 to accommodate the large number who will wish for a last view of one they always had reason to call their friend.

The city of Cortland, so distraught at the loss of such a kind and generous man, turned out in droves. Even the serving Mayor, John C. Barry, publicly declared that every business in Cortland would close for one hour during Chester Wickwire’s funeral. Each and every business willingly complied.

The death of Chester F. Wickwire is a shock to this community beyond words to express. No pen, no spoken word can adequately express the sorrow in the hearts of all citizens of this city over the news of Mr. Wickwire’s decease. That we as a city have suffered a great loss, how greatly only the future can determine, is an acknowledged fact. I deem it fitting and proper to request that during the hours of Mr. Wickwire’s obsequies that all business places of every character, including all our factories, suspend business and work, as a mark of sorrow and in recognition of Mr. Wickwire’s worth as a successful and benevolent fellow citizen.

John C. Barry, Mayor

(Cortland Standard, September 14, 1910)