Here unfold the wild tales of the life of David L. Brainard. Within its records, you will discover the torrid, but true recounting of epic adventures, mutiny, starvation, suicide and perhaps even cannibalism. This dreadful story is not for the faint of heart. Read on … if you dare.

Location #1: Childhood Home of David L. Brainard at 1912 McGraw Marathon Rd, Marathon, NY 13803

(42.50136803432869, -76.03383639323398)

Future site of New York State Historical Marker honoring the childhood home of David. L. Brainard, by efforts of the Cortland County Historical Society and Marathon Historical Society.

David L. Brainard, the fifth of Alanson and Maria’s seven children, was born on December 21, 1856. When David Brainard was 10, his parents moved the family from Norway, NY, to a bucolic corner of Cortland County. Here, Alanson and Maria built an idyllic homestead and dairy farm they would call home for the rest of their lives.

Young David Brainard spent his mornings and evenings diligently assisting with the milking chores, his afternoons studying at Cortland Normal School, and every bit of free time galloping through the hills of Freeville and Marathon.

Later in life, these hours spent exploring the rugged countryside astride the strong backs of his beloved horses would serve him well. Unimagined even to him, David Brainard would one day serve with the calvary in the American-Indian Wars, Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American war.

Location #2: Marathon Train Deport at 14 W Main St, Marathon, NY 13803 (42.44076711981125, -76.03752984402655)

The Adventure Begins

On September 13, 1876, 19-year-old David L. Brainard stood before this very depot. He would board a train heading to Philadelphia, never anticipating how his adventure to visit the Centennial Expedition World’s Fair would change his life and the course of history.

Wandering the fair, Brainard explored the displays honoring the country’s crowning achievements in industry and agriculture. In a fateful twist of foreshadowing, the U.S. Naval Observatory’s Arctic exhibit featured a much darker subject – the haunting relics salvaged from the failed Franklin Expedition. Known as “The Lost Expedition,” 134 souls departed England in 1845 on a voyage of Artic exploration, never to return.

On Brainard’s return home to Marathon, he too would discover himself on a misadventure. When changing trains in New York City, he reached into his wallet only to find his money missing. Too proud to wire his parents for the funds, he hopped a free ferry to the US Army Post at Governor’s Island and impulsively enlisted.

Perhaps inspired by his elder brother’s service, he dutifully tried on his new Army Uniform, only to find the missing ten dollars secreted in his shirt pocket. Nonetheless, he was Private David Brainard now!

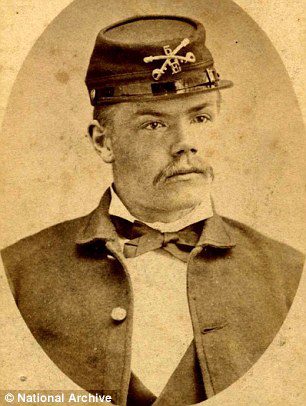

Brainard served diligently and with honor, moving up the ranks to Sergeant. Brainard yearned for the freedom of civilian life despite his successful military career. Although he hesitated to re-enlist, the allure of an Artic adventure was too strong. The misplaced $10 he’d saved for a discharge celebration would be tucked away for another time. Brainard volunteered for the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition in 1881, with First Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely appointing him as First Sergeant and Commissary Sergeant.

By all accounts, the first two years of the expedition were a tremendous success, even when the first resupply ship failed to arrive. Scrupulously recorded data (sometimes collected by the hour) consisting of readings and observations in weather temperature, wind, ice and snow collected by the crew from 1881-1883 are still used in scientific research today.

On May 14, 1883, Brainard and his closest friend on the expedition, Lt. James B. Lockwood, set the record for farthest north (latitude 83º 24’ N., longitude 40º 46’W). From base camp, they journeyed over 200 miles, on foot and sled, through storms and plunging temperatures. As proof of his accomplishment, Brainard left the motto for his favorite beer scrawled into the cliffside. It read ‘Plantation Bitters – Started in Trade in 1860 with Ten Dollars’ and was likely a nod to the $10 bill that had altered his life. This record would stand for another 13 years.

On this expedition, Brainard would set the record for exploring the farthest north, east and west in the Arctic. On foot and sled, though horrific conditions, Brainard had managed to bravely journey one-eighth of the distance around the world above the 80th parallel.

When the promised relief ship failed to arrive for a second year in 1883, Greely made a quick decision to follow the predetermined emergency plan. On August 9, with just a few hours’ warning, the crew abandoned the relative safety of their base camp to embark on a perilous journey 250 miles south down the coast to Cape Sabine, in an attempt to intercept the rescue ship. Leaving behind their dogs and most of their supplies, they loaded basic rations and all their scientific records into tiny dingies. They launched into waters so dangerous the rescue ships could not navigate them. Overwhelmed with fear, the crew nearly mutinied.

September 29, 1883, after failing to intercept the rescue ship or find the promised food caches, Greely was forced to change course. Battered by a violent ocean, half their scant previsions lost, the ragged crew made landfall along the shore of Baffin Bay, thirty miles from Cape Sabine. Alas, Eskimo Point, as Greely would name it, proved to provide anything but a safe harbor, after all.

Location #3: Marathon Historical Society at 11 Brink Street, Marathon, NY 13803

(42.43925479514148, -76.03402151472903)

Marathon Historical Society is open by appointment. Please call (607)-849-3170 to schedule a tour.

A Thief Among Men

By Brainard’s calculations, when the wretched crew arrived at Cape Sabine on October 22, they only had 35 full days’ rations of bread and meat to carry 25 men through the following summer. And the men were already hungry.

October 20, 1882, the 25 men of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition laid their boat as a roof over the hut built of ice and stone that would serve as their winter quarters. The infinitesimal shack, measuring a mere 25 feet long by 18 feet wide and just four feet high, would host the entirety of the desperate crew until either the bay froze, rescue arrived, or, at worst, they all died. It wouldn’t be long before their tight quarters revealed a traitor in their midst.

Shortly after they settled in, Brainard found a snow block on the exterior wall of the lean-to storehouse tampered with, making it removable so that an arm might reach in to fill a gnawing belly.

What follows are the details of the next 7 months as recorded in David Brainard’s personal journal (The Outpost of the Lost, originally published in 1929) –

November 15: Someone broke into the commissary last night…

November 17: I have placed a wooden door with a lock in the commissary storehouse, which will be an effectual bar to all midnight intruders.

Brainard’s journal entries go on to reflect a man who continued to seek joy and gratitude, despite the direness of his situation –

November 21: A bounteous repast this morning with which everyone was well pleased, consisted of stewed seal skins and fox intestines, thickened with moldy dog biscuit. Nothing in our cuisine department is ever wasted, not even the cleanings of the fox intestines.

November 22: Another stew was thickened with rotten dog biscuit. I believe that the meanest cur in the streets would have refused it, but to us it is life.

As winter bore down on them, successful hunting crawled to a halt, and the temperatures continued to plummet.

December 31: This craving, the continual gnawing at my stomach is horrible. It brings with it visions of the most tempting dishes.

January 7: This morning I discovered that one of the barrels of English bread had been broken into and about 5 pounds bred stolen.

In desperation, Brainard attempted to booby trap the lauder by installing a loaded spring gun, but he couldn’t guarantee it would work. Nonetheless, he left it in place, hoping to frighten the thief. Clearly, the thief was fearless. Chocolate and personal provisions continued to disappear amidst the dwindling resources. Yet, despite his labors, Brainard refused to take more than his share.

January 8: Lieut. Greely offered me an increase of one ounce of bread per day, over the others, on account of the irksome duties which I have to perform. Although weak and sadly in need of it, I refused on the ground of injustice to my comrades. I will take my chances with them.

Brainard and the crew continued to work daily, chipping ice for fresh water, hunting and scavenging the windswept and bitter landscape they called Camp Clay.

Sergeant William H. Cross was the first to die. Scurvy and malnutrition were the culprit.

January 18: One cannot conceive of anything more unearthly, more weird, than this ghostly procession of emaciated and half-starved men moving slowly and silently away from their wretched ice-prison in the dim and uncertain light of an Arctic night, having in their midst a dead comrade who was about to be laid away in the frozen ground forever. It was a scene that one can never forget.

January 19: Mercury frozen again.

January 20: Mercury is lost sight of in the bulb.

February 11: Since our water hole gave out a month ago, we have not had drinking water, and we cannot spare the fuel with which to melt ice. Several of the men begged for water today, but there is not a man among us with strength enough to find and start another freshwater hole.

February 13: The last of our rice went today. The provision will extend to March 12th at least.

The thief continued without compassion, but Brainard’s suspicions were keenly fixed upon his identity.

February 14: A small piece of butter was found missing from a can sitting on the shelf in the boat [which was acting as the roof]. Henry keeps his candle molds on the same shelf.

Determined not to let the crew starve, Brainard devised a clever plan. On March 17, he cobbled together an apparatus to catch what he called shrimp, but we now know as sea lice.

Location #4: CNY Living History Center at 4386 Route 11, Cortland NY 13045 (42.619744, -76.183271)

A Thief Revealed

On a bitter March morning, the group’s cook, exhausted by his slow starvation, forgot to remove the vent cover. Oily smoke from alcohol and wet kindle filled the hut, making the men sick and causing a tremendous commotion that would reveal the cruel traitor by the end.

March 23: During the excitement about a half pound of bacon was stolen…To think that in our midst was a man with a nature so devoid of humanity as to steal food from his starving companions when they might be dying. A deed so contemptible and so heartless could not remain concealed. We were not disappointed in the discovery that Henry was the thief. He had bolted the bacon which was more than his enfeebled stomach could bear. The bacon was quickly ejected before our eyes and Henry’s crime revealed. Threats of lynching were privately made.

Upon this discovery, Greely issued that Pt. Charles B. Henry should be kept confined, without access to the space nearest the larder, in an effort to protect the meager stocks.

By April 5, several men refused to eat the “shrimp” any longer, as it was nearly impossible to digest. According to Brainard, “by actual count, 700 shrimp weigh an ounce. They possess little nutrient; about three-fourths is shell and one-fourth meat.”

That day, Frederick Thorlip Christiansen was the second to die of starvation.

April 9: I took inventory of provisions this morning with the following result: meat of all kinds, 156 pounds; bread 70 pounds. And on this we expect to prolong life another month until May 10th. The future is dark and gloomy. I think that Artic clouds are seldom seen with silver lining.

That day, Lockwood breathed his last. Brainard was forced to bury his constant companion, whom he considered a brother. He wrote, “This is the saddest duty I have ever yet been called upon to perform.”

April 16: Henry has been paroled and given the limits of the peninsula.

April 19: The greatest difficulty I have to contend with in my duties about camp is the issue of fresh meat which frozen firmly, has to be cut with a hand saw. I am too weak for even this simple task. I often feel like giving up.

April 23: This life is horrible! I am afraid that we will yet all go mad.

In a tragic accident on April 24, the expedition’s hunting rifle, kayak and best hunter, Jen Edwards, were lost to the sea – with them, the crew’s remaining hope.

April 27: Henry made the issue of diluted alcohol [used for cooking fuel] today without authority, stealing enough to the precious fluid to make himself disgustingly drunk. He is a born thief.

May 1: Previsions for only 9 days remain. Lieut. Greely asked our individual opinion as to the extension of our provisions beyond the date already agreed on. The majority were in favor of reducing them to the minimum.

May 2: We see our doom impending and even look forward to death as a relief from suffering. Our rations have been reduced to eight ounces per man.

May 7: Many, including myself, spent the greater portion of the day inditing farewell letters to friends and relatives.

May 12: I issued the last of our provisions today. The issue consisted of twelve and a half ounces of bacon and tallow to each man. This is intended to last for two days, but if they chose can be consumed at once. Heaven only knows what we will do now. Present indications are that we can do nothing but-die.

The remaining crew were left to survive on the sea lice and lichen they might forage. By May 26, they were reduced to eating their seal skin garments, which had to be locked away in the storehouse to prevent further theft.

May 31: Of all the days of suffering, none can compare with this. If I knew I had another month of this existence, I would stop the engine as this moment.

By early June, twelve had died. Most devastatingly, their only doctor, Octave Pavy, was amongst the dead. In sheer desperation, Pavy consumed the remaining narcotics from the medicine chest, effectively ending his own life.

Twice more, Henry would be found stealing. On June 5, he was caught eating seal skin from the public lot.

June 5: The stealing of seal skin boots etc. may seem to some a very insignificant affair, but to us such articles mean life.

The extra shrimp Henry pinched from the breakfast pot on June 6 would prove to be his last.

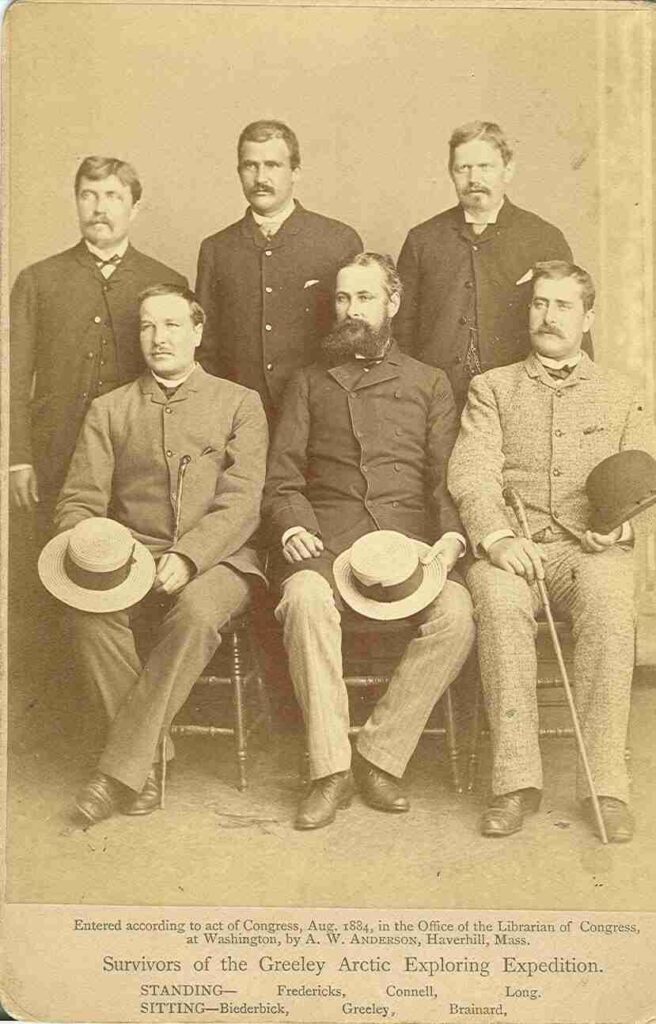

Under Lt. Greely’s orders, Brainard, Fredricks and Long (the three strongest among the survivors) were to execute Henry by firing squad. According to Brainard’s records, the only serviceable rifles in the camp were of different calibers, so the usual military procedure of loading with two balls and one blank cartridge was not an option. Nonetheless, two shots rang across the desolate landscape, signaling its completion.

Greely immediately ordered a search of Henry’s personal items. There they discovered 12 pounds of sealskin, Sgt. Long’s seal skin boots and various scientific instruments.

Later Brainard would pen, “Fredericks Long and myself agreed that only one of our numbers should fire. I have sometimes been asked which of us that was. […] three of us took an oath before the event never to tell on earth who fired the shots. Fredricks and Long are dead. They never told who shot Henry and I never shall.”

Unbeknownst to the men, Private Charles B. Henry was on the expedition under an alias. His legal name was Charles Henry Buck. Previously, Henry, while enlisted at Fort Buford, had forged his commanding officer’s signature on several orders for food supplies in an effort to commandeer a large sum of meat. Upon discovery, Henry was sentenced to two years of hard labor. The conniving inmate managed to escape after having served just one. Adopting his new name, Henry hung his hat in Dakota Territory for a while before murdering a Chinese American in Deadwood over a gambling debt. Once again on the lam, Henry decided there was no safer place to hide than back within the safe fold of the military. Eventually, Captain George T. Price, Henry’s commanding officer and a friend of Lt. Greely, would recommend Henry for the arctic expedition. Henry would be the last man to sign on to the ill-fated Lady Franklin Bay Expedition.

Location #5: Country Blessings Café at 10 E Main St, Marathon, NY 13803 (42.441160, -76.034301)

After the Marathon Fire Department decommissioned this building, it became the home of the Marathon Independent, Marathon’s longest-running newspaper. Edgar Adams, both propitiator, editor and writer, published Marathon Independent here for over sixty years until his death.

A Belated Rescue

“The news of the rescue of the Greely expedition, which was first received here last Thursday afternoon, generated great excitement in this village, where one of the survivors of the party, Serg. David L. Brainard was well known.”

The tidings of this local newspaper, not a phone call nor an official letter, shared the joyous news of their son’s rescue with his parents, Alanson and Maria Brainard. Before even sitting down to pen the celebratory news, Edgar Adams, the president of the Marathon Independent made his way alongside postmaster Charles A. Brooks to the Brainard farm on Freetown Road.

According to the Marathon Independent (July 23, 1884):

“After exchanging a hearty ‘Good afternoon,’ the visitors informed Mr. Brainard that they had some news for him. ‘Is that so? What is it?’ ‘They have found your boy.’ At this Mr. and Mrs. Brainard walked down close to the wagon. They longed yet feared to know more. The suspense was broken when the further information was offered. ‘He is alive and well.’ The look of assured joy that broke over the faces of these good people as this last sentence was spoken to them is something that the writer will never forget, and the consciousness of having been a party, even in a small way, to the producing of this happiness will long be a source of gratification to us.”

On June 22, 1884, too weak to lift a pen to paper, Brainard lay trapped beneath the collapsed shelter and swore he heard a ship’s whistle. The camp lay in shambles, the starved men unable to make repairs against the relentless weather of the Arctic. Under Brainard’s urging, the emaciated camp cook, Francis Long, crawled to the fallen signal flag. Mustering the last of this strength to lift it, a US Navy ship spotted the lost men.

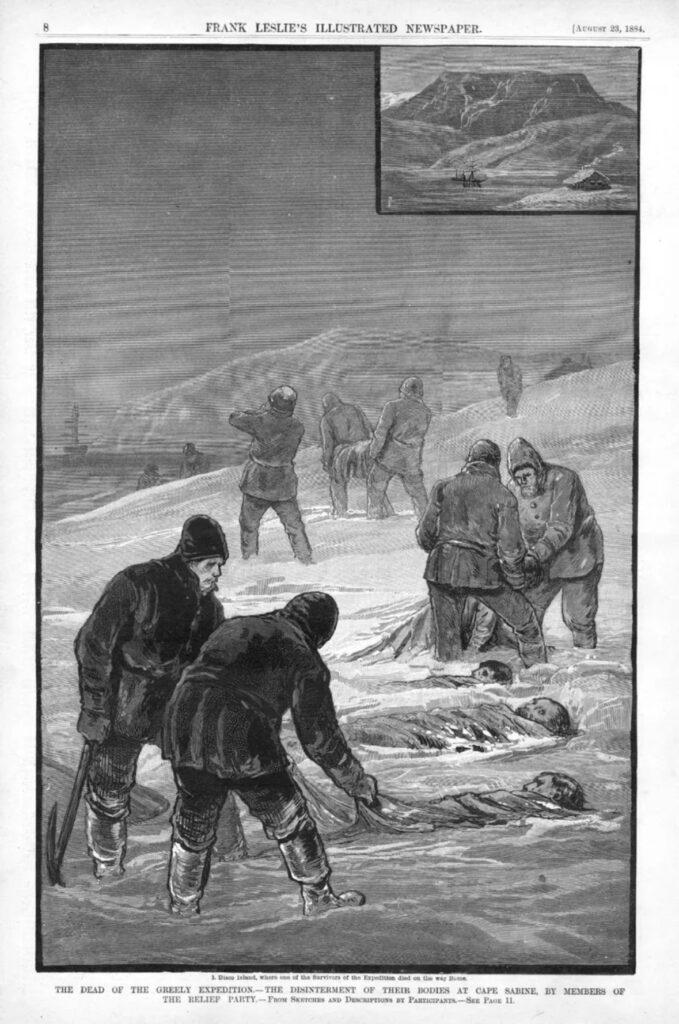

Navy Commander Winfield Scott Schley would soon make a gruesome discovery. Death had stalked the crew of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition without mercy. Of the 25 original members, only seven had survived, and each was a mere 48 hours from death.

Some bodies lay scattered about camp, the survivors too malnourished to move them. Others lie windswept under gravel and ice along what the crew dubbed Cemetery Ridge. Still, others were swept forever out to sea. After carefully securing the survivors aboard the ship, the Naval crew had the ghastly duty of retrieving the bodies of the fallen. Upon collecting the corpses, it was discovered that their flesh had been cut from the bones. As for the traitor Henry, his head had been decapitated and lost by what the survivors could only assume had been an animal.

Adolphus Greely, Julius Frederick, David L. Brainard, Henry Bierderbick, Maurice Connell and Francis Long would be the only survivors to return home. Joseph Ellison, the seventh survivor, who had clung to life for weeks with a spoon tied to the remaining stump of his hand, was beyond saving. He had lost his feet and pieces of his hands to frostbite and gangrene. Doctors aboard the rescue ship amputated Ellison’s hands and legs, but it was in vain. Upon his death, Ellison weighed just 78 pounds.

News of the mutilated bodies reached the shore before the survivors did. According to New York Times (August 18, 1884), “Some of the men [deceased] had been little more than skin and bones when they died, but the flesh they had was gone in places, as on the calves of the legs, on the hips, thighs, and arms. Some of this, it is thought, was used as bait for the shrimps, some to sustain the wasting life of the survivors.”

On August 14, shortly after the funeral of Lt. Frederick Kislinigbury, upon his bother’s insistence, an autopsy was performed prior to burial. Undertaker L. A. Jeffreys determined that flesh had indeed been cut from the bones post-mortem, confirming the macabre accusations.

Lt. Greely, Brainard and the surviving crew ardently denied any knowledge of cannibalism, nor was any hint of it recorded in any of the crews’ mandatory diaries.

Over time, theories and rumors continued to bubble up, including accusations of cannibalism against Henry. Though most commonly, it is believed that when the bait ran out, some members secretly used human remains to trap sea lice in a desperate search for substance.

“The scenes which occurred there may never be fully known. The secrets of those awful days are locked in the hearts of the little handful of survivors.” New York Times August 18, 1884

Location #6: Marathon Cemetery at Galatia St, Marathon, NY 13803

(42.44680, -76.03206)

David L. Brainards parents, as well as many additional family members, are buried in Marathon Cemetery. Alanson Brainard is buried in Section 12, Lot 1, and Maria Ann Legg Brainard is buried in Section 12, Lot 1. In many cases, a tree stump gravestone was chosen to symbolize a life cut short.

The Marathon Independent wrote on July 23, 1884, that “During a conversation with him [David L. Brainard] at the time, told us that he had been offered by another soldier $300 [equivalent to nearly $9,000 today] for his chance to go [on the arctic expedition], but so anxious was he for the trip that no money would tempt him to abandon it.”

In retrospect, one might wonder if Brainard might have regretted not accepting the offer.

Brainard’s father, Alanson, would pass on March 12, 1887. Just a few years later, he would lose his mother, Maria, on January 13, 1891, at 66. Brainard’s parents each passed on the family farm and lie buried here at Marathon Cemetery.

Local newspapers show that Brainard regularly visited his family and no doubt grieved their passing deeply. However homesick he might be, Brainard continued to serve his county whenever he was called to duty. Brainard viewed his remaining time as a gift meant to be spent in service.

Despite the tragic outcome of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, Brainard is credited with saving as many of his fellow crew members as possible by his meticulous rationing of limited resources. Brainard would continue to selflessly come to the aid of those in distress. In December 1897, he assisted starving Klondike gold miners during a bold Yukon relief mission. Moving steadily up the ranks, Brainard retired as a Brigadier General in October 1919, 35 years after his rescue from Camp Clay.

Brainard outlived his parents by 23 years. During that time, he remained in close contact with Lt. Greely. Each year, on June 22, Brainard and Greely would share a meal to honor their rescue and those lost. They made a point to choose dishes that the men had spoken longingly of back at Camp Clay, especially from the elaborate fanciful menus of Lockwood. Brainard was near his side when Greely passed on October 20, 1935.

Brainard’s love for adventure never faded, despite his horrific arctic journey. In 1904, he became one of the founding members of the infamous Explorers club, eventually serving as its president. On his 80th birthday, he would become the first honorary member of the American Polar Society.

The last remaining survivor to die, David L. Brainard, passed away at 90 on March 22, 1946, a life well lived in adventure and service.

Lt. Greely, ever Brainard’s champion, once wrote:

“As an American soldier his extraordinary services and unswerving fidelity during the fateful winter at Cape Sabine preserved lives, maintained solidarity, and eventually led to the preservation of the records of the first scientific cooperation of this country. His diary that winter is a document of geographical work, not only marked by literary style but also a record of duty done, and an example worthy of emulation by his successors.”

Sources

1. Library, Dartmouth College. “Introduction to the Brainard Camp Clay Diary.” Introduction to the Brainard Camp Clay Diary, 29 Sept. 2017, https://www.dartmouth.edu/library/digital/collections/manuscripts/brainard-diary/introduction-camp-clay-diary.html. Accessed 3 April, 2023.

2. American Experience, PBS. “Members of the Greely Expedition.” American Experience | PBS, 21 Aug. 2018, www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/greely-bios.

3. “Shame of the Nation.” New York Times, 18 Aug. 1884, www.nytimes.com. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

4. “The Second in Command Lieut. Kislingbury’s Mulated Body Disinterred.” TimeMachine New York Times, New York Times, 14 Aug. 1884, timesmachine.nytimes.com. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

5. Frcgs, Glenn M. Stein Frgs. General David L. Brainard, U.S. Army: Last Survivor of the United States’ Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (1881-84). 1 Jan. 2008, www.academia.edu/20395013/General_David_L_Brainard_U_S_Army_Last_Survivor_of_the_United_States_Lady_Franklin_Bay_Expedition_1881_84_.

6. Brainard, David L. The Outpost of the Lost: An Arctic Adventure. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

7. Levy, Buddy. Labyrinth of Ice: The Triumphant and Tragic Greely Polar Expedition. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2021.